Sinners in the Hands of an Angry or a Gentle God?

by Fr. George Morelli

In 1965 Roger Brown made perhaps the most important discovery of modern linguistic theory. He reported that whenever we speak, the tone of voice and the manner in which words are spoken (technically called the pragmatics of communication or onomatopoeic analysis) do more to determine meaning of words than the definitions of the words themselves.

Brown concluded that if something is said in an angry or mean tone, the tone is communicated rather than the words. For example, if someone came into the room and the host said softly, “sit down,” the words would be heard as an invitation. The guest would feel welcomed and perhaps appreciated and certainly open to listening to his host.

On the other hand, if the host barked out, “sit down!” in a harsh and inconsiderate manner, the guest would most likely respond emotionally, perhaps experience some hurt or confusion, and would likely infer the host was mean-spirited. The guest will close himself off to any forthcoming messages. Psychological research confirms this conclusion (Morelli, 2006).

How we preach the Gospel influences how it is heard

Brown’s discovery has important implications including how we hear the Gospel. Take the title of the fiery sermon preached by the early American preacher Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God for example. Consider too the tone of Edward’s message illustrated in this brief quotation:

The wrath of God burns against them, their damnation does not slumber; the pit is prepared, the fire is made ready, the furnace is now hot, ready to receive them; the flames do now rage and glow.

Clearly Edward’s harsh tone and emphasis on anger portrays a vengeful and merciless God. Based on my years of counseling experience however, other titles might fit as well: Children in the hands of an angry parent, spouses in the hands of angry spouse, workers in the hands of an angry boss, citizens in the hands of an angry civil authority, laity in the hands of an angry priest, priests in the hands of an angry bishop, bishops in the hands of an angry patriarch. Edward’s conception of God’s relationship to mankind in other words, mirrors the relationship many people have with angry authority figures.

If we follow Brown’s discovery, Edward’s angry tone can mute and even distort the Gospel message. The scriptures reveal however, that Christ most often took a gentle approach toward His hearers. His words were intoned with love and consideration, not anger and wrath.

St. Matthew writes:

And Jesus went about all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues and preaching the gospel of the kingdom, and healing every disease and every infirmity. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; pray therefore the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest” (Matthew 9:35-38). (Emphasis added.)

Compassion is defined as “a sad concern.” The Gospel writers record Jesus expressing compassion nine times. St. Matthew records Jesus saying, “I am gentle and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29).

In the Sermon on the Mount Jesus said, “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.” He also said, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Matthew 5:9). Those who are “meek” are described as showing patience, humility, gentleness. Peacemakers use a gentle and soft voice.”

Jesus is never harsh and strident. He is never shown as argumentative by the gospel writers. When an argument broke out around Jesus, He “. . . perceived the thought of their hearts, he took a child and put him by his side. . .” St. Luke tells us (Luke 9:47).

Children are drawn to gentleness and it is unlikely that a child would allow himself to be next to such a man. St. Matthew records, “Then children were brought to him that he might lay his hands on them and pray. The disciples rebuked the people, but Jesus said, “Let the children come to me, and do not hinder them; for to such belongs the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 19: 13-14).

This is hardly the “angry God” that Edwards taught.

The reaction of Jesus to the death of Martha and Mary’s brother Lazarus also deserves mention. St. John writes:

“Where have you laid him?” They said to him, “Lord, come and see.” Jesus wept. So the Jews said, “See how he loved him!” But some of them said, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?” Then Jesus, deeply moved again, came to the tomb; it was a cave, and a stone lay upon it. Jesus said, “Take away the stone.” Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, “Lord, by this time there will be an odor, for he has been dead four days . . . And Jesus lifted up his eyes and said, “Father, I thank thee that thou hast heard me. I knew that thou hearest me always, but I have said this on account of the people standing by, that they may believe that thou didst send me . . . (John 11: 34-39, 41-42).

Once again it is inconceivable that the Christ of scripture was driven by anger.

One gospel account shows the Lord as angry. St. Matthew writes:

And Jesus entered the temple of God and drove out all who sold and bought in the temple, and he overturned the tables of the money-changers and the seats of those who sold pigeons. He said to them, “It is written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer’; but you make it a den of robbers” (Matthew 21:12-13).

While anger is expressed in this passage, it is too easy to portray Jesus as enraged; shouting and cursing the profiteers as He overturned their tables. A more plausible explanation is that Jesus was in complete self-control, firmly excoriating the money-changers while driving his words home with his actions, a point confirmed in the next passage that reveals He was immediately approached by the blind, lame, and children. St. Matthew writes:

And the blind and the lame came to him in the temple, and he healed them. But when the chief priests and the scribes saw the wonderful things that he did, and the children crying out in the temple, “Hosanna to the Son of David!” they were indignant; and they said to him, “Do you hear what these are saying?” And Jesus said to them, “Yes; have you never read, ‘Out of the mouth of babes and sucklings thou hast brought perfect praise?'” (Matthew 21:14-16).

The blind, lame, and children would never approach an enraged man. More likely, Jesus exemplified Theodore Roosevelt’s adage to “speak softly but carry a big stick.”

Further, if any justification for anger exists in the life of Christ it would be during His arrest, scourging, and crucifixion. The brutality of Christ’s passion is described by the holy evangelists (Matthew 26-27; Mark 14-15; Luke 22-23; John 18-19).

Consider the peace and gentleness of heart and spirit of Jesus when he said while hanging on the cross, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). Consider too His meekness when he said to the penitent thief hanging on a cross next to Him, “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43). Consider as well Christ’s silence in the face of Pontius Pilate who ultimately sentenced Him to death. Orthodox theologian Veselin Kesich (2004) writes, “The most dominant feature of the Passion narrative is precisely this silence of Christ.”

Applying the virtues of Christ to our life

Kindness, gentleness and love do not begin and end in Our Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ. His life is meant as a guide for us. We are to imitate Him who said, “I am gentle and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29).

St. Paul exhorts the Colossians, “Put on then, as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassion, kindness, lowliness, meekness, and patience, forbearing one another and, if one has a complaint against another, forgiving each other; as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive” (Colossians 3: 12-13). Why would St. Paul give such an instruction unless Jesus Himself was compassionate and kind?

St. Paul writes to the Romans “. . .love one another with brotherly affection; outdo one another in showing honor. . .” (Romans 12:10). Spiritual writer Fr. Lawrence Lovasik (1999) says that outward courtesy is the expression of inner affection. He points out courtesy is treating others with “deference and respect” because they are made in God image. “It involves politeness, patience, thoughtfulness, helpfulness and kindness.”

Jesus told us, “For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also. . .The good man out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil man out of his evil treasure produces evil; for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks” (Luke 6: 21, 45). St. Paul told the Romans to be patient in tribulation, practice hospitality, bless those who persecute you and do not curse them, rejoice with the joyful and weep with the sorrowful, live in harmony with one another and “if possible, so far as it depends upon you, live peaceably with all” (Romans 12: 12-18).

The Orthodox fathers confirm the gentleness of Christ in their lives as well. Irenee Hausherr (1990) notes:

The two elements of this kindness, humility and charity, are often found in the most famous spiritual fathers. One example will suffice. An axiom approved by St. Anthony states: “It is not possible for a man to be recalled from his purpose thorough harshness, because one demon does drive out the another. Rather, you will bring the lost one back through benevolence, for our God draws man to himself through counsel.”

Humility, not anger, reflects the true disposition of Christ

In Orthodox Christianity, icons are known as “windows to heaven” (Zelensky and Gilbert, 2005). The icon (eikon or image in Greek) is a sacred image in Orthodox faith and practice because it affirms the created materiality and historical specificity of Christ and the Saints. It shows that the Incarnation of Christ, and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in the Saints is not a literary allusion but a concrete event in space and time.

St. John Damascus, an early apologist for the use of icons wrote, “(There) is clearly a prohibition against representing the invisible God. But when you see Him who has no body become man for you, then you will make representations of His human aspect. . .When He who, having been the consubstantial image of the Father emptied Himself by taking the form of a servant (Philippians 2:6-7). . .taking on the carnal image, then paint and make visible to everyone Him who desired to become visible” (Ouspensky, 1978).

While the words of John of Damascus may be a bit difficult to comprehend in our day, his meaning is nevertheless simple. Think of it this way: If cameras were around in the days of Christ, His image would appear in any photograph taken of Him. Christ was not a phantom or ghost, but a flesh and blood human being like every other person but at the same time being fully God. Thus, like the photograph, an icon of Christ does not violate the commandment against “graven images,” because the image represented is the visible Incarnate Christ but not the invisible God.

At the same time, icons have a stylistic dimension that directs contemplation not towards the physical characteristics of their subjects, but rather toward their spiritual virtues. These virtues have their source and origin in God (the “fruits” of the Holy Spirit according to St. Paul), but can be appropriated and expressed through the Holy Spirit that empowers man to obey the commandment to love his neighbor. The icon, then, functions in a different way than the photograph. It is meant to bring us into awareness, and finally the presence, of God by directing our minds to higher things that ultimately lead to repentance and life in Christ. This is one way that icons are “windows into heaven.”

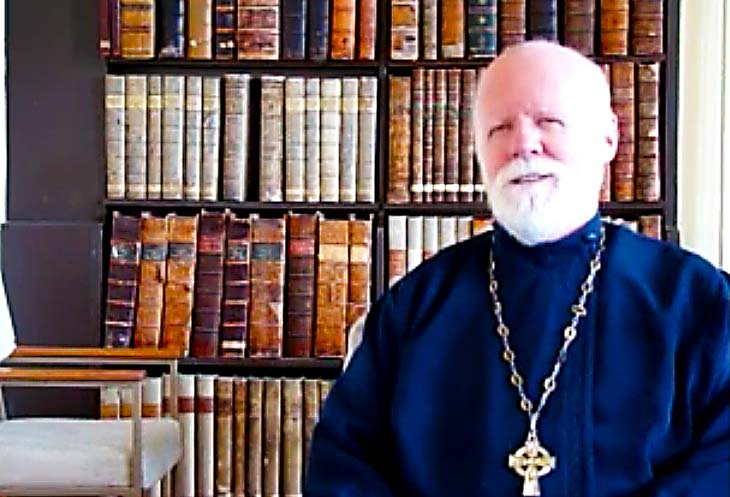

Contemplate the following icon of Our Lord God, and Savior Jesus Christ, depicting His “Extreme Humility.” Meditate on it well:

Does the Savior of Mankind appear as an angry God? Or does He appear as a God of mercy, love, and kindness?

A contemporary elder of Mt. Athos relates an event from his earlier life. Elder Paisios, resolved a youthful crisis by saying to himself: “Based on the fact that He [Christ] is the kindest man on earth and I haven’t known anyone better, will try to become like Him and absolutely obey everything the Gospel says” (Priestmonk Christodoulos, 1998).

How then, do we reconcile hell with a loving God? Was Edwards correct or did he miss something important? Archimandrite Sophrony (1999) provides an answer in the following encounter between a hermit and the Staretz (elder):

The hermit “declared with evident satisfaction that ‘God will punish all atheists. They will burn in everlasting fire.'”

Obviously upset, the Staretz said, “Tell me, supposing you went to paradise, and there you looked down and saw someone burning in hell-fire – would you feel happy?”

“It can’t be helped. It would be their own fault,” said the hermit.

The Staretz answered him in a sorrowful countenance. “Love could not bear that,” he said. “We must pray for all.”

The God of humility consigns no one to hell. Rather, hell is the place of those who rebel against God; a place freely chosen by those who despise the presence of God and the condition of those who refuse the mercy of God.

The key to the Gospel of Christ is love. We are not “sinners in the hands of an angry God” but sinners in the hands of a gentle and loving God.